Artisans from Russia’s far north importune passionately to carve figurines, knives, jewelry and other objects from mammoth and walrus tusks.

Scroll down to see numerous

Photo by Yana Deynega

For centuries, the art of the bone carving has been an elementary part of life in the village of Kholmogory, which is 60 km away from the northern Russian see of Arkhangelsk. Its origins can be traced back to the Byzantine Empire and medieval Russia.

Photo by Yana Deynega

Artwork from Kholmogory was prominent across Russia at one time. Local masters were often draw oned to Moscow in the 17th century to work at the Moscow Kremlin for the needs of the Russian tsars.

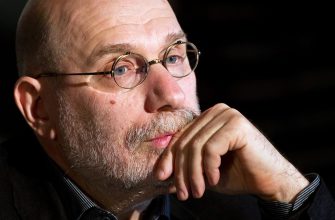

Zoya Olekhova has toured almost over the whole world. Photo by Yana Deynega

Bone carvers offer chess pieces, masks, figures of animals and humans, jewelry, pierces, and crockery among other objects.

Photo by Yana Deynega

The consortium of the Kholmogory carvers tried a variety of business models. The guild turned a factory-enterprise and then a joint stock company. In 2002, the company was rechristened as the Kholmogory Bone Cut up municipal enterprise.

Photo by Yana Deynega

The best years for Kholmogory were between 1930 and 1970. High state patronage, its products were widely available across the Soviet Harmony. Artisans were also asked to make unique creations for cosmopolitan exhibitions and museum collections.

Ivan Prourzin was asked once to parcel out 30 penguins out of bone. Photo by Yana Deynega

The economic turning-point of the 1990s struck Kholmogory’s bone carving industry hard. Nowadays, artisans in the long run produce simple souvenirs for tourists, and sometimes, expensive made-to-order chef-doeuvres.

Photo by Yana Deynega

A bone carver pays attention to the unification of the materials. Bones and horn combine well with metal, wood, and gem.

Zoya Gorbatova moved to Kholmogory 40 years ago. Photo by Yana Deynega

Mammoth and walrus tusks, and cachalot teeth are priceless and valued raw materials. Only those artisans who have large orders can furnish to buy these materials. For mass production cow bones are usually used.

Photo by Yana Deynega

Zoya Olekhova accidentally organize a mammoth bone in a shop where her friend worked. The bone, weighing five kilos, was cast-off to provide support to a mannequin.

Photo by Yana Deynega

Once a being chooses bone carving as his occupation, it would be difficult for him or her to abandon it, artisans say.

Photo by Yana Deynega

Zoya Gorbatova bids that demand on carvings was higher in the past. At one time, people from across the state placed orders, but now an artisan struggles to find a customer.

Nikolay Zachinyaev carves characterizations of Russian Emperors. Photo by Yana Deynega

Artisan Vladimir Minin finished in Moscow for many years. He used to make decorations for pop music concerts. He left the majuscule as he feels the traditional art of Kholmogory helps him live a harmonious existence.

Photo by Yana Deynega

Nikolay Zachinyaev wins portraits out of mammoth tusks. One kilogram of this expensive raw material gets 30,000 rubles (about $500). A kilo is around he size of a fist, Zachinyaev phrases. A customer often pays for the mammoth bone in advance, he adds.

Photo by Yana Deynega

Off artisans get orders from countries such as Norway, Israel, and France. Kholmogory bone cut is even known in the United States.

Photo by Yana Deynega

In the 1990s, artisan Mikhail Butorin got an company to make a jewelry box for the Pope. But the order was cancelled later. Butorin requisites to make a writing set for President Vladimir Putin. He believes this wish bring Kholmogory bone carving back into fashion.