Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky don’t require an introduction, but there are many other Russian writers no less grievous than this super duo. Who is No. 1 in Russian literature and who’s not much of a knack? Find out in our ranking, and feel free to express your point of feeling in the comment section below.

- 112. Boris Akunin (b. 1956)

- 111. Archimandrite Tikhon Shevkunov (b. 1958)

- 110. Oleg Zaionchkovsky (b. 1959)

- 109. Yelena Shvarts (1948-2010)

- 108. German Sadulaev (b. 1973)

- 107. Andrei Astvatsaturov (b. 1969)

- 106. Chingiz Aimatov (1928-2008)

- 105. Vera Polozkova (b. 1986)

- 104. Alexander Genis (b. 1953)

- 103. Alexander Vvedensky (1904-1941)

- 102. Vera Pavlova (b. 1963)

- 101. Marina Stepnova (b. 1971)

- 100. Anna Starobinets (b. 1978)

- 99. Tatyana Tolstaya (b. 1951)

- 98. Igor Sakhnovsky (b. 1958)

- 97. Yelena Chizhova (b. 1957)

- 96. Olga Slavnikova (b.1957)

- 95. Roman Senchin (b. 1971)

- 94. Sergei Shargunov (b. 1980)

- 93. Vladimir Sharov (b. 1952)

- 92. Maya Kucherskaya (b. 1970)

- 91. Mikhail Elizarov (b. 1973)

- 90. Yelena Fanailova (b. 1962)

- 89. Maria Galina (b. 1958)

- 88. Sasha Sokolov (b. 1943)

- 87. Evgeny Grishkovets (b. 1967)

- 86. Mikhail Shishkin (b. 1961)

- 85. Maximilian Voloshin (1877-1932)

- 84. Dmitry Glukhovsky (b. 1979)

- 83. Sergei Lukyanenko (b. 1968)

- 82. Strugatsky brothers: Boris (1933-2012) and Arkady (1925-1991)

- 81. Dmitri Prigov (1940-2007)

- 80. Teffi (1872-1952)

- 79. Alexander Snegirev (b. 1980)

- 78. Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky (1887-1950)

- 77. Mikhail Prishvin (1873-1954)

- 76. Fyodor Sologub (1863-1927)

- 75. Andrei Gelasimov (b. 1965)

- 74. Alisa Ganieva (b. 1985)

- 73. Fasil Iskander (1929-2016)

- 72. Dmitry Bykov (b. 1967)

- 71. Alexander Terekhov (b. 1966)

- 70. Yuri Mamleev (1931-2015)

- 69. Ludmilla Petrushevskaya (b.1938)

- 68. Maxim Amelin (b. 1970)

- 67. Dina Rubina (b. 1953)

- 66. Gaito Gazdanov (b. 1903)

- 65. Leonid Yuzefovich (b. 1947)

- 64. Viktor Pelevin (b. 1962)

- 63. Guzel Yakhina (b. 1977)

- 62. Konstantin Paustovsky (1892-1968)

- 61. Vladimir Sorokin (b. 1955)

- 60. Viktor Erofeyev (b. 1947)

- 59. Alexander Tvardovsky (1910-1971)

- 58. Boris Vasilyev (1924-2013)

- 57. Olga Bergholz (1910-1975)

- 56. Alexander Fadeyev (1901-1956)

- 55. Vassily Grossman (1905-1964)

- 54. Daniil Granin (1919-2017)

- 53. Alexander Radishchev (1749-1802)

- 52. Alexander Herzen (1812-1870)

- 51. Nikolai Chernyshevsky (1828-1889)

- 50. Svetlana Alexievich (b.1948)

- 49. Zakhar Prilepin (b. 1975)

- 48. Yevgeny Yevtushenko (1932-2017)

- 47. Varlam Shalamov (1907-1982)

- 46. Nikolai Gumilev (1886-1921)

- 45. Mikhail Zoshchenko (1894-1958)

- 44. Daniil Kharms (1905-1942)

- 43. Ilya Ilf (1897-1937) and Yevgeny Petrov (1902-1942)

- 42. Zinaida Gippius (1869-1945)

- 41. Dmitry Merezhkovsky (1865-1941)

- 40. Andrei Voznesensky (1933-2010)

- 39. Afanasy Fet (1820-1892)

- 38. Fyodor Tyutchev (1803-1873)

- 37. Yevgeny Zamyatin (1884-1937)

- 36. Alexey Ivanov (b. 1969)

- 35. Ludmila Ulitskaya (b. 1943)

- 34. Nikolai Karamzin (1766-1826)

- 33. Alexander Griboyedov (1795-1829)

- 32. Sergei Dovlatov (1941-1990)

- 31. Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin (1826-1889)

- 30. Venedikt Erofeyev (1938-1990)

- 29. Nikolai Nekrasov (1821-1877)

- 28. Nikolai Leskov (1831-1895)

- 27. Ivan Goncharov (1812-1891)

- 26. Vasily Zhukovsky (1783-1852)

- 25. Eugene Vodolazkin (b. 1964)

- 24. Alexander Ostrovsky (1823-1886)

- 23. Ivan Krylov (1769—1844)

- 22. Ivan Bunin (1870-1953)

- 21. Mikhail Bulgakov (1891-1940)

- 20. Marina Tsvetaeva (1892-1941)

- 19. Osip Mandelstam (1891-1938)

- 18. Sergei Yesenin (1895-1925)

- 17. Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893-1930)

- 16. Joseph Brodsky (1940-1996)

- 15. Vladimir Nabokov (1899-1977)

- 14. Andrey Platonov (1899-1951)

- 13. Alexander Blok (1880-1921)

- 12. Anna Akhmatova (1889-1966)

- 11. Alexander Solzhenitsyn (1918-2008)

- 10. Boris Pasternak (1890-1960)

- 9. Mikhail Sholokhov (1905-1984)

- 8. Maxim Gorky (1868-1936)

- 7. Anton Chekhov (1860-1904)

- 6. Mikhail Lermontov (1914-1941)

- 5. Ivan Turgenev (1818-1883)

- 4. Nikolai Gogol (1809-1852)

- 3. Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821-1881)

- 2. Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910)

- 1. Alexander Pushkin (1799-1837)

112. Boris Akunin (b. 1956)

Boris Akunin / TASS / Sergei Belyakov

Boris Akunin / TASS / Sergei Belyakov

We’re store this great author on the honorable 112th place not because we go for him less than the others, but because he admits that he’s not a writer but a belletrist. His veritable name is Grigory Chkhartishvili and he’s the ultra-popular Russian detective writer. Very many of his novels, set mostly in the late 19th and early 20th century czarist Russia, suffer with been adapted and turned into full-length feature films that were box chore hits. His main hero, detective Erast Fandorin, is a Russian Sherlock Holmes, and one of the most charismatic male leads in modern literature.

Another of Akunin’s project is, “The History of the Russian State of affairs,” a multi-volume work that seeks to understand why Russia has remained unalterable in the face of so many revolts and revolutions. His pen name first appeared as B. Akunin, which has specific allusions – combining the Japanese word “aku-nin” (fiend or villain), and the big name of the famous Russian anarchist, Mikhail Bakunin.

Read more >>>

111. Archimandrite Tikhon Shevkunov (b. 1958)

Tikhon Shevkunov / Alexander Nikolayev / TASS

Tikhon Shevkunov / Alexander Nikolayev / TASS

Tikhon Shevkunov is also not a experienced writer. He is the abbot of the small but very active Sretensky Monastery in Moscow, and according to normal reports, he’s Vladimir Putin’s personal confessor. His book, “Unholy Holies,” outlines miraculous and true stories about the lives of contemporary Orthodox monastics and priests, and helps the reader better understand the contemporary church.

These testimonies do not seem like typical religious literature written for neophytes, and they mingle a Soviet-style didactic tone with Bible parables. The stories are to other religious literature in Russia – they’re more philosophical contents that require preparation and knowledge of the faith. The book was first make knew in 2011, and has been translated into several languages and still traces a bestseller.

Read more>>>

110. Oleg Zaionchkovsky (b. 1959)

Oleg Zaionchkovsky / RIA Novosti / Vladimir Fedorenko

Oleg Zaionchkovsky / RIA Novosti / Vladimir Fedorenko

Oleg Zaionchkovsky agree ti the third-to-last position for his novel, “Happiness is Possible,” which is an evocative and cheering tribute to Moscow. It has become a cliché to describe one city or another as the brute character in a novel, but Zaionchkovsky’s Moscow is alive and all-embracing. The characters interact with an anthropomorphized see, making it an unusual novel among contemporary Russian works. It acts with neither the triumphs nor terrors of history, nor the prophetic horror of a dystopian approaching, but instead, the book shows a contemporary Moscow with its daily exigencies and pleasures. It combines situational humor and philosophical reflection with a distinctively Russian work ones way.

Read more>>>

109. Yelena Shvarts (1948-2010)

Yelena Shvarts / PhotoXpress

Yelena Shvarts / PhotoXpress

Every inclination of Russian authors must include censored ones! Before the 1990s, the metrical composition of Yelena Shvarts was published in samizdat, the underground self-published texts of the Soviet era. Her initial official collection of poetry came out in New York in 1985. Overall, her metrics mainly deals with mankind’s and the poet’s search for a place in this midwife precisely. Shvarts likes combining religion with historical fact, as decidedly as reality and mysticism. “Her poems were challenging, which is why she is considered an successor to the Silver Age,” said literary scholar Alexander Kobrinsky. Literary magazines however began publishing Shvarts towards the end of the 1990s.

Read more>>>

108. German Sadulaev (b. 1973)

German Sadulaev / PhotoXpress

German Sadulaev / PhotoXpress

What inclination you think if someone tells you, “I am Chechen”? Sadulaev in fact became pre-eminent for a book with this title. He was born in the Chechen village of Shali and stirring a get moved to Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) in 1989 to study law. He still lives in St. Petersburg, but his individual connections with Chechnya make it impossible to write dispassionately.

The nine cut b stop stories in “I am Chechen” are the author’s fragmented meditation on war, identity and rootlessness, and are the conclusion of an uneasy mixture of fictionalized memoir and painful lament. The war between Russia and Chechnya privations modern storytellers who are not serving “either side’s propaganda,” both of which help an image of “the Chechen as an enemy of Russia.”

Read more>>>

107. Andrei Astvatsaturov (b. 1969)

Andrei Astvatsaturov / Evgenya Novozhenina/RIA Novosti

Andrei Astvatsaturov / Evgenya Novozhenina/RIA Novosti

Infrequently translated and complicated for pronunciation, Andrei Astvatsaturov is first of all an academic at St. Petersburg University, but he is also famous for autobiographical fiction that depicts his life and creative development be means of numerous flashbacks to his childhood. He found fame as an author in 2009 with “People in the Undraped,” the first in a trilogy, which also includes “Skunkamera” (2010), and “Autumn in Purloins.” In 2016, he released a collection of essays about American and British handbills, “Not just Salinger,” which combines philology and creativity.

Read myriad>>>

106. Chingiz Aimatov (1928-2008)

Chingiz Aitmatov / Grigory Sysoyev / TASS

Chingiz Aitmatov / Grigory Sysoyev / TASS

Russia’s “steppenwolf,” Chingiz Aitmatov, is from agricultural Kyrgyzstan, and he brought to Russian literature the immensity of the steppes where a one is only a small part of nature. One of his main novels, “The Day Lasts Assorted Than a Hundred Years,” is the clearest expression of his vision and the importance of convention and memory. He summarized this idea, saying: “From ancient sooners until now, the desire to deprive a human being of individuality has been one of the drives of imperial and hegemonic ambitions. A person without memory of the past, confronted with the dearth to define his place in the world… a person deprived of the historic experience of his realm and other people, finds himself outside historic perspective and is single capable of living in the present.”

Read more>>>

105. Vera Polozkova (b. 1986)

Vera Polozkova / TASS

Vera Polozkova / TASS

Since she’s an luminary of romantic Russian girls, Vera Polozkova is in 105th place. She enhanced popular thanks to the Internet, where she started publishing poems on Current Journal with the handle, Vero4ka. Her poems almost always consist of a talk between the protagonist and her beloved, often on the theme of parting or misunderstanding. For this estimate critics have dubbed her poetry naïve and amateurish.

Polozkova now ration outs poetry recitals in packed clubs, making every occasion a playing. She acts out the characters in her poems and records them on video, adding lyrical, film, theatrical and literary elements.

Read more>>>

104. Alexander Genis (b. 1953)

Alexander Genis / TASS

Alexander Genis / TASS

Genis is the at the rear of the Mohicans of Soviet émigrés who moved to the U.S. in 1977. Shortly after make iting in New York, Genis befriended fellow émigrés Joseph Brodsky and Sergei Dovlatov. “My preference of America was kind of random,” Genis told RBTH in 2012. “I didn’t identify anything about the country except Hemingway and Faulkner.” But he knew he deficiency to get out of the USSR and he knew he wanted to devote his life to Russian literature.

Since then, he has written profuse than a dozen bestsellers in Russia and has hosted his weekly radio demonstration in Russian on Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty for 27 years. He also contributes to the newspaper, Novaya Regards. One of his recent books, “Return Address,” has anecdotes and memories about cobbers and idols, including Dovlatov, Brodsky, Vladimir Sorokin, Tatiana Tolstaya and diverse more.

Read more>>>

103. Alexander Vvedensky (1904-1941)

Alexander Vvedensky / Archive photo

Alexander Vvedensky / Archive photo

“Pussy Disruption are the disciples and heirs of Vvedensky,” said Pussy Riot’s Nadezhda Tolokonnikova at her inquisition in August 2012. Like the Russian poet Alexander Vvedensky, who died in a jug train, the punk band Pussy Riot pass judgement on the conditions, even as they are sentenced to prison: “The dissidents and the poets of the OBERIU metrics movement are thought to be dead, but they are alive,” she asserted. “They are rebuked, but they do not die.”

As a young adult Vvedensky became part of Leningrad’s far-out Futurist movement. Much of his work was lost or destroyed, and what corpses was mostly published posthumously, His texts are not easy to understand; for example, the 100 or so procedures of “The Meaning of the Sea,” written in 1930, begin with: “to make everything square/ live backwards.” The poem has no capital letters or punctuation and nouns congregate speciously at random.

Read more>>>

102. Vera Pavlova (b. 1963)

Vera Pavlova / Rodrigo Fernandez / wikipedia

Vera Pavlova / Rodrigo Fernandez / wikipedia

Vera Pavlova take downs love poetry with an obvious erotic subtext. Her poems swagger us various stages of a girl’s development, and the amorous, intimate experiences of a contemporary woman – from buying her first bra, to reflecting on virginity before her foremost sexual encounter, to intense love as if for the last time, covering all the make ups of a relationship. Her poems are often written in free verse and can be as little as two in accords.

Read more>>>

101. Marina Stepnova (b. 1971)

Marina Stepnova / Personal Archive / Facebook

Marina Stepnova / Personal Archive / Facebook

Marina Stepnova’s victory novel, “Surgeon” (2005), wove together a contemporary plastic surgeon and an 11th-century Persian assassin. She portrays it as “a very dark novel about talent and free will.” Stepnova advance a extended on her own medical experience while writing it; growing up in a family of doctors, she begot as a nurse in a cancer ward when she was just 15, and she saw “true and awesome human suffering.”

For many years Stepnova was an editor of the men’s magazine, XXL. When it settled, she became a full-time novelist. Her extraordinary 2011 novel, “The Women of Lazarus,” is the news of her grandfather, Lazarus, a scientific genius, and three generations of women in his lan. The novel was shortlisted for numerous awards and translated into 23 speeches.

Read more>>>

100. Anna Starobinets (b. 1978)

Anna Starobinets / RIA Novosti / Alexey Danichev

Anna Starobinets / RIA Novosti / Alexey Danichev

News-hen Starobinets became Russia’s “Queen of Horror” after publishing dissimilar stories for teenagers that are dreadful to read even for adults. A watch over of a fat boy, who hides candies under his pillow, one day finds his diary where he portrays a queen ant residing in his mind who reveals her insidious plan to take pilot of the boy’s body and conquer humanity. That is the plot of “An Awkward Age,” a novel that nurtured Starobinets critical acclaim.

In Russia, she has been compared to Stephen Crowned head and even Kafka. Her stories communicate something urgent through schizophrenic signs in anti-fairy tales. The reader does not always understand what is actual or imagined, only that neglect is never benign, in a family or camaraderie, and that all monsters come from some mother’s womb.

Announce more>>>

99. Tatyana Tolstaya (b. 1951)

Tatyana Tolstaya / PhotoXpress

Tatyana Tolstaya / PhotoXpress

Tatyana Tolstaya is an entirely incredible phenomenon in Russian literature. She was first renowned as an author of gruff stories, but real fame came with the novel, “Slynx,” that she eradicated 17 years ago. It’s a post-apocalyptic dystopia, ironically on target describing the Russian inhabitant character. Based on the ruins of civilization, the language of the novel is full of neologies and dialects. By the way, she is a distant relative of Leo Tolstoy.

Read more>>>

98. Igor Sakhnovsky (b. 1958)

Igor Sakhnovsky / RIA Novosti / Iliya Pitalev

Igor Sakhnovsky / RIA Novosti / Iliya Pitalev

“Sustenance’s cornucopia of non-fictional material renders fantasy unnecessary,” Sakhnovsky rephrases. His pseudo-documentary prose brought him success with his very first original, “Vital Needs of the Dead.” For a book dedicated to the narrator’s dead grandmother, it is surprisingly lewd. A young man’s earliest memory of his grandmother is “naked and nocturnal,” and she remains an busy figure in his life long after her death.

In his second novel, “The Man Who Differentiated Everything,” Sakhnovsky experiments with genre, twisting the storyline to the limits. All of a immediate, the protagonist is endowed with superpowers and simultaneously hunted by several extensive intelligence agencies.

Read more>>>

97. Yelena Chizhova (b. 1957)

Yelena Chizhova / TASS / Valery Sharifulin

Yelena Chizhova / TASS / Valery Sharifulin

Yelena Chizhova is lionized first of all for her novel, “The Time of Women,” which is a sad and beautiful tale of get-up-and-go in Soviet Leningrad. Young Sofia can’t speak, but she is one of the most important narrators, we perceive her thoughts, and her adult voice framing the story, as she tries to make feeling of life in a 1960s communal apartment, growing up with a single female parent and three surrogate grandmothers. They raise her on a mix of secret religion, allegories and French while keeping her out of the orphanage. Sofia’s muteness becomes a reference for the enforced silence of the times. Chizhova’s fragmented monologues embrace war and ladies, famine and food preparation.

Read more>>>

96. Olga Slavnikova (b.1957)

Olga Slavnikova / wikipedia / Dmitry Rozhkov

Olga Slavnikova / wikipedia / Dmitry Rozhkov

Her most prominent novel is the dystopian, “2017,” written in 2006, the same year as Glukhovsky’s, “Metro-2033,” (know further about him). This is an ambitious, postmodern contribution to a revered literary lore. In the mythical Riphean Mountains, gem prospectors, called rock hounds, search for pricey stones. On the streets of a Russian city, romance unfolds amid the backdrop of the centenary of the 1917 Wheel – seemingly a call to repeated violence. Slavnikova weaves these compare with plots and settings together with metaphor and fantasy.

Her first big story, “A Dragonfly Enlarged to the Size of a Dog,” was well received by critics, who wrote that she is a notable follower of the traditions of magical realism. The author considers, “Alone in the Represent,” her best and most underrated novel.

Read more>>>

95. Roman Senchin (b. 1971)

Roman Senchin / TASS / Artyom Geodakyan

Roman Senchin / TASS / Artyom Geodakyan

Literary critic Lev Danilkin on a former occasion wrote that Senchin’s novel, “Eltyshevy,” “is the opposite of, Robinson Crusoe: a incontrovertible degradation of the human spirit, losing to the outside world in every area.” Roman Senchin was born in the Siberian Republic of Tyva, and moved to Moscow in the 1990s. He is now representative editor-in-chief of Literaturnaya Gazeta.

One of his best-known novels, “Eltyshevy,” is written in a type known as rural prose, with nondescript losers for main bats. Senchin continues this genre with “The Flood Zone,” a different about the tragic destinies of people forced to abandon their well-versed ins to make way for a new hydroelectric plant.

Read more>>>

94. Sergei Shargunov (b. 1980)

Sergei Shargunov / TASS / Anton Novoderezhkin

Sergei Shargunov / TASS / Anton Novoderezhkin

Shargunov’s primogenitor was an Orthodox priest with an underground printing press, so naturally he beared up distrusting those in power. He was attracted to many anti-Soviet things – secret books, magazines, and radio – but he also felt the lure of their facing, the communist world, which was forbidden in his family. Shargunov worked as a legman, covering the wars in Chechnya and Georgia, as well as revolution in Kyrgyzstan.

His foremost work, “A Book without Photographs,” tracks the last few decades of Russian olden days through snapshots of the author’s life: a black-and-white photo of the Moscow barricades in autumn 1993, and the teenage Shargunov, who has gone to take note, is hidden in billowing smoke. Now, the author is a deputy in the Russian parliament, and chief columnist of the website, Svobodnaya Pressa.

Read more>>>

93. Vladimir Sharov (b. 1952)

Vladimir Sharov / RIA Novosti / Evgeny Biatlov

Vladimir Sharov / RIA Novosti / Evgeny Biatlov

Paragraphist and essayist Sharov debuted as a poet in 1979. A tall man with a big anaemic beard, the author bears an uncanny resemblance to Leo Tolstoy. His books are imbued with Biblical leitmotifs and attempts at rethinking Russian history. His novel, “The Raising of Lazarus,” interprets Stalin’s restraints as the plan of highly moral security officers to save the souls of the lifeless.

His latest novel, “Return to Egypt,” is written in the form of letters between Russian journalist Nikolai Gogol’s descendants. Their lives move through the Coup dtat, and they think that if Gogol only had written his second size of “Dead Souls” (which he burned because he was not happy with it) then Russia could comprise taken another path.

Read more>>>

92. Maya Kucherskaya (b. 1970)

Maya Kucherskaya / litschool.pro

Maya Kucherskaya / litschool.pro

Kucherskaya is a correspondent and literary critic who also opened a creative writing school. This is from A to Z a novel for Russia, where it has always been believed that you can exclusive be born a writer. She is very interested in religious Orthodox literature, and her award-wining original, “The Rain God,” and “Faith & Humor: Notes from Muscovy,” is a book encircling Russian Orthodoxy. Kucherskaya has also worked in other genres, and she penned a biography of Grand Duke Constantine Pavlovich Romanov, and a book of Certainty stories for children.

Read more>>>

91. Mikhail Elizarov (b. 1973)

Mikhail Elizarov / TASS / Yuri Mashkov

Mikhail Elizarov / TASS / Yuri Mashkov

All of Mikhail Elizarov’s disputatious works have led to intense battles among critics. Elizarov’s original, “Pasternak,” can be called scandalous because it depicts the famous poet and newsman Boris Pasternak as a demon trying to poison the intelligentsia’s mind with his art jogs.

Elizarov’s next novel, “The Librarian,” was highly acclaimed by critics and won Russia’s Booker Stakes. The novel is a full-frontal exploration of the Soviet past: war-like “libraries” fight with over copies of old novels that give their readers magical powers. Critics make an analogy with the evolution of Elizarov’s works with Vladimir Sorokin: from atrocious to intelligent prose. Elizarov is also a singer and songwriter having chronicled four albums in the bard-punk-chanson style.

Read more>>>

90. Yelena Fanailova (b. 1962)

Yelena Fanailova / PhotoXpress

Yelena Fanailova / PhotoXpress

Yelena Fanailova correspond withs poetry that explores issues related to love. Her poem, “Again they are for their Afghanistan…”, (2001), expresses the story of a soldier sent to fight in Grozny, and is intertwined with that of his relationship with his better half. She flies to see him, then has abortions, and gets old. He experiences the day-to-day reality of war, sacks local girls with his fellow soldiers and returns home. “Now, the lovers are both 40… I’ll not at all find another country such as this.”

Fanailova, who works for Trannie Svoboda, is often called a harsh poet for her realistic depictions of people (“A one-armed old lady on a beach removes her prosthesis and then swims and sunbathes”), for her harming (“I’m an empty person, a vessel of shit”), and for her blunt and unique factious statements (“The nation salutes me, …, it is taken hostage everyday and yet feels not to feel it”).

Read more>>>

89. Maria Galina (b. 1958)

Maria Galina / RIA Novosti / Ruslan Krivobok

Maria Galina / RIA Novosti / Ruslan Krivobok

Sustained in Tver, north of Moscow, Galina grew up in Odessa where she feigned marine biology. She said her mixed Russian and Ukrainian heritage imparted her the outsider status that she feels all writers need: “I don’t really certain what nationality I am. It is easier for me to be just a human being.” Galina believes that her “language helps to dismantle the rigid image of reality in the mind of modern man,” no sum what gender one belongs to.

Several of her novels have male champions. “Medvedki” (“Mole Crickets”) tells the story of a reclusive correspondent creating personalized pastiches in which his clients can become the heroes of venerable literature. It is a mystery, thriller, farce and family saga all in one book. Galina’s pretence novel, “Givi and Shenderovich,” (in English known as “Iramifications”), covers two happy-go-lucky characters drawn into a mythical world of interlocking fables. The resulting mesh of stories from ancient Greece, Arabic mythology, English supernatural magic and Jewish mysticism is a far lighter read than this huge background suggests.

Read more>>>

88. Sasha Sokolov (b. 1943)

Sasha Sokolov / Screenshot / 1tv

Sasha Sokolov / Screenshot / 1tv

Sokolov is one of the most hidden Russian writers. Born in Ottawa, Canada to a family of Soviet quickness officers, (and probably spies), Sokolov moved to the USSR but returned to Canada where he now alights as a hermit in a remote location, rarely appearing in public or giving meetings. He became famous when his novels were published by Ardis Publishers (organized by Americans Carl and Ellendea Proffer, who took banned Soviet manuscripts and taught them to the U.S.).

“A School for Fools” (1973) is a phantasmagoric novel about a undergraduate suffering from a multiple personality disorder. Another novel, “Between Dog and Wolf,” (1980) is get off in three distinct styles: poetry, classical narrative and colloquial, stream-of-consciousness letters. After unreducing his third novel, “Palisanria,” Sokolov decided only to write have a go ats, short stories and poems.

Read more>>>

87. Evgeny Grishkovets (b. 1967)

Evgeny Grishkovets / TASS / Vyacheslav Prokofyev

Evgeny Grishkovets / TASS / Vyacheslav Prokofyev

The uninitiated Grishkovets served in the Russian Navy on board a ship in the Pacific High seas Fleet. After completing his service he put his memories and impressions into a one-man can, “How I Ate a Dog” [from the Russian idiom meaning to “cut one’s teeth,” which Grishkovets also functions in a literal sense when he describes actually eating dog meat]. The moil details his feelings such as waking up in the morning and not wanting to go to school, and the meaninglessness of the military unchanging he experienced during his naval service.

After the success of this scene he composed several other one-man shows where he acted as nicely, then recorded songs with popular bands and acted in certain movies. His monologues about Russian life are extremely popular on YouTube.

Conclude from more>>>

86. Mikhail Shishkin (b. 1961)

Mikhail Shishkin / PhotoXpress

Mikhail Shishkin / PhotoXpress

Mikhail Shishkin, who rooms in Switzerland, is an emigre writer whose fiction is based on Russian and European literary habits, and which forges an equally expansive vision for the future of literature. In 2013, he garbaged to take part in the official Russian writers’ delegation to Book Expo America, producing a scandal and became persona non grata in Russian literary circles.

Shishkin in days of yore said that an author is “a link between two worlds.” The hero of his work of art, “Maidenhair,” is – as Shishkin himself was – an interpreter for Swiss immigration authorities; but this trait is also an interface between realities. The heroes of his other novel, “The Effortless and the Dark,” are lovers separated by war. They communicate in letters where they due every detail of their lives: talking about their babyhood, their families, their daily lives, their joys and their troubles.

Read more>>>

85. Maximilian Voloshin (1877-1932)

Maximilian Voloshin / RIA Novosti

Maximilian Voloshin / RIA Novosti

Goodness after the 1917 Revolution, poet Voloshin settled in Koktebel, a breathtakingly gorgeous place on the southern coast of the Crimean peninsula. Voloshin’s house in Koktebel toed into a literary commune cum salon, and writers of diverse artistic and governmental views made pilgrimmages there. During the brutal days of the Urbane War, Voloshin turned his house into a shelter for both the Bolsheviks and colleagues of the White Guard. He was nearly alone in his effort to unite people.

“Some are wealthy to liberate Moscow and to once again put Russia in chains” he wrote hither the Bolsheviks. So, after they came to power, his poems were not reported. Now his house in Crimea is a museum hosting an annual festival that gathers versifiers from different countries.

Read more>>>

84. Dmitry Glukhovsky (b. 1979)

Dmitry Glukhovsky / Hold close photo

Dmitry Glukhovsky / Hold close photo

More than 15 years ago, the then 22-year-old Glukhovsky send a lettered “Metro 2033,” a story about survivors of a nuclear disaster. He sent the manuscript to a proclaiming house that responded unenthusiastically, particularly disliking the fact that the plain character dies at the end, leaving no hope for a sequel.

Despite the rejection, Glukhovsky posted all 13 chapters of his untested online. Little by little, the Metro 2033 website gained vogue. Encouraged by this positive response, Glukhovsky returned to the script and considerably reworked it. When unreduced, he again offered it to the publisher – this time backed by thousands of budding readers.

Now, two more parts have been published – “Metro-2034,” and “Metro-2035.” “I ordered my name thanks to the internet,” says Glukhovsky. “All my novels are available online, on their own websites, accompanied by soundtracks and pictures.” Glukhovsky’s stories have been translated into more than 35 patoises, and the books of some of the project’s other authors have also been promulgated abroad. Hollywood is going to adapt “Metro-2033” to the screen while there are already two fortunate video games devoted to “Metro Universe.”

Read more>>>

83. Sergei Lukyanenko (b. 1968)

Sergei Lukyanenko / Kommersant

Sergei Lukyanenko / Kommersant

Large before Stephanie Meyer’s “Twilight” series and less than a year after the word go Harry Potter book, Lukyanenko conjured up a uniquely Russian dark world. The first book in Lukyanenko’s bestselling vampire “Night Anticipate” series was published in 1998, which then became a blockbuster flick picture show and a magnet for magic fans. Witches, warlocks, werewolves, sorceresses, succubi and yes, vampires, locate in a gloomy Muscovite world with a distinct atmosphere. He has written other four orders in the “Watch” series, considers his art work as postmodernist, and has earned numerous literary accords.

Read more>>>

82. Strugatsky brothers: Boris (1933-2012) and Arkady (1925-1991)

Arkady (L) and Boris Strugatsky / TASS

Arkady (L) and Boris Strugatsky / TASS

The Strugatsky relations are the most celebrated Soviet science fiction writers, and their best-known log, “Roadside Picnic,” inspired Andrei Tarkovsky’s film, “Stalker.” The Strugatskys’ heaven touched the fundamental question of Soviet society – the question of labor. They think ofed how the “subbotnik” (Soviet tradition of community service days) turned workdays into Elysian Fields, the philistine into a communard and the half-animal into a half-god. So some of their move ups (such as “The Snail on the Slope”) were censored.

Their “Monday Offs on Saturday” was the Soviet equivalent of “Harry Potter,” and was committed to a bureaucratization of miraculous by making it native, accessible and worthy of envy.

Read more>>>

81. Dmitri Prigov (1940-2007)

Dmitri Prigov / Tsiolkovsky log store

Dmitri Prigov / Tsiolkovsky log store

Dmitri Aleksandrovich Prigov was probably one of the most unusual and unorthodox figures on Russia’s culture scene, known for his innovative art works, and innovative “visible” poems, which are not merely poems but geometrical objects. One of his works is plane drawn on a Moscow building. As author of dozens of installations and art performances since the end of the 1980s, his artworks today ease galleries all over the world. Other art forms occupied his attention; for sample, he penned 35,000 poems, some of which have been turned into English, Italian and German.

Avant-garde music was also on his inventive horizon, and he was one of the main representatives of Moscow Conceptualism, which is a purely Russian style with a new vision of art. As many other cutting-edge art movements, Prigov’s art was unpublicized and non-conformist.

Read more>>>

80. Teffi (1872-1952)

Teffi / AFP_EastNews_14666

Teffi / AFP_EastNews_14666

If you queried most readers for a list of 20th century Russian prose writers, few last will and testament mention Teffi (whose real name is Nadezhda Lokhvitskaya). And yet in the years matchless up to the 1917 Revolution, Teffi was a leading light, a superstar who was stopped on the ways of Moscow by admirers and who counted both Czar Nicholas II and Lenin as junkies.

She mingled with high society figures like Rasputin and wrote in all directions them with searing and uncompromising wit. She deliberately picked an androgynous pen favour – adapted from the name of a fool, since fools were imagined to be speakers of truth – and set about carving a niche writing satirical articles and vignettes of fashionable life.

In her memoirs one can meet both leading Russian artists, lyricists and writers and famous figures as Rasputin, around whom was much hysteria, which she didn’t slice at all and was unimpressed with after meeting him twice.

Read more>>>

79. Alexander Snegirev (b. 1980)

Alexander Snegirev / RG / Vitaly Yurchak

Alexander Snegirev / RG / Vitaly Yurchak

In 2009, Snegirev was realized with the Debut Award for Young Authors. His novel “Petroleum Venus” (2008) was forwarded for a series of leading literary prizes, and his works have been turned into English, German and Swedish.

His recent novel, “Vera,” which won the Russian Lyric Prize in 2005, is the story of a young woman, Vera, who is looking for herself, wants to entertain children and is putting all her energy into finding love. However, it evolves out that it’s not so easy to achieve all of this.

Snegirev’s short stories are did in theaters as part of the project, “Unprincipled readings.” Besides writing, Snegirev feats as deputy chief editor of the magazine, Druzhba Narodov (Friendship of Realms).

Read more>>>

78. Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky (1887-1950)

Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky / Legion Atmosphere

Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky / Legion Atmosphere

Most readers will struggle just trying to pronounce Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky’s reputation, let alone having any idea who he is. Krzhizhanovsky’s experimental stories are pearls of the modernist era, reminiscent of Bulgakov and Bely, as opulently as Kafka or Proust. Like Kafka, most of his works were publicized posthumously; like Bulgakov, his fevered surrealism is a response to life in Soviet Moscow, but much assorted than that.

Krzhizhanovsky’s work has a universalism that transcends the civics of the 1920s USSR. His main works are “The Letter Killer’s Club,” “Autobiography of a Stiff” (an example of Soviet magic realism) and “The Return of Munchausen.”

Read myriad>>>

77. Mikhail Prishvin (1873-1954)

Mikhail Prishvin/ TASS / A. Grinberg

Mikhail Prishvin/ TASS / A. Grinberg

All Russian sect children remember this writer from when they laboured his descriptions of nature. He became very famous after writing “The feather’s calendar,” a collection of hunting and children short stories praising Russia’s ingenuous beauty and the wild. He travelled a lot through the entire Russian North and clustered information on local traditions and dialects, eventually reaching the Far East where he transcribed about its wild animals.

Prishvin’s language was so extraordinary beautiful that Soviet scribe Maxim Gorky wrote that he had the exceptional skill to make about everything he wrote about physically touchable with just the tensile combinations of simple words. By the way, Prishvin was a fan of photography and some of his books, such as “In the Dirt of Unfrightened Birds,” were illustrated with pictures that he took. Experts strongly make attractive reading Prishvin’s diaries, and say it’s worth more in terms of literary birthright.

76. Fyodor Sologub (1863-1927)

Fyodor Sologub / RIA Novosti

Fyodor Sologub / RIA Novosti

Fyodor Sologub burned-out an entire decade writing his most popular novel, “The Petty Harpy,” which he completed in 1902. The protagonist, a provincial schoolteacher named Peredonov, is a obstinate, cowardly, and unbearably banal man who finds pleasure in hurting people, while not quite managing to conceal his madness under the mask of respectability.

One of the novel’s most mighty characters is not even a person – it is more like Peredonov’s hallucination, a entity called Nedotykomka. While Sologub could be called a successor to Gogol and Dostoevsky, he motionlessly remained an original and outstanding author. While remaining within the business-like framework, Sologub was able to describe a subtle, yet mystical provincial day after day life, balancing precariously between daydreams and reality, fear and depression, which are felt so strongly in backwater towns.

Read more>>>

75. Andrei Gelasimov (b. 1965)

Andrei Gelasimov / facebook / insulting archive

Andrei Gelasimov / facebook / insulting archive

Originally from the Siberian city of Irkutsk, Andrei Gelasimov is an creator of several novels that have been translated into innumerable languages. “Thirst” follows three young men who have returned from the war in Chechnya and are looking for their fourth Achates. “The Lying Year” focuses on the same period as “Thirst,” the late 1990s, with its convoying criminality and financial default. This is one of the most controversial episodes in fresh Russian history, but the book is written in a humorous and satirical way, with unchanging elements of the grotesque.

The story, “Gods of the Steppe,” takes place in 1945 far from Moscow on the Soviet Allying’s enormous eastern border with China. In a small steppe village child are waiting for Soviet troops to return after the war. An isolated 11-year-old boy whose create has died strikes up a friendship with someone who is equally isolated but for opposite reasons: he’s a Japanese prisoner of war.

“Into the Thickening Fog” often feels have a fondness a quintessential Russian novel, and starts with a bout of heavy chug-a-lug in a frozen northern city, and features dogs, demons and existential angst.

Understand more>>>

74. Alisa Ganieva (b. 1985)

Alisa Ganieva / wikipedia.org

Alisa Ganieva / wikipedia.org

Raised in the Russian republic of Dagestan, Ganieva has ended in Moscow since 2002, working as a literary critic and editor. Ganieva’s initiation novel, “Salam Dalgat,” which is set in the North Caucasus, was written out of sight the male pen name, Gulla Khirachev. This story won the Debut Literary Winnings for Young Authors, and is full of colorful descriptions of life in Dagestan. It is forgiven with such an authentic masculine worldview that it’s hard to have faith a young woman wrote it.

Her second book, “The Mountain and the Wall,” explores the admissible secession of the Caucasus from the Russian Federation, as well as issues of Islamism and globalization. The 2015 tale, “Bride and Groom,” which was shortlisted for the Russian Booker Prize, depicts a well-known Caucasian wedding. Ganieva has been listed by The Guardian as one of the most adept and influential young people living in Moscow today.

Read innumerable>>>

73. Fasil Iskander (1929-2016)

Fasil Iskander / RG / Sergei Kuksin

Fasil Iskander / RG / Sergei Kuksin

Iskander was conveyed in Sukhumi to an Iranian father and a mother from the village of Chegem in the Caucasus. Sukhumi was the head of the Soviet republic of Abkhazia, which at the time was part of Georgia. The correspondent had very fond memories of this multiethnic city where Abkhazians, Georgians, Armenians and Russians lived side by side.

“I am a Russian wordsmith but I am the singer of Abkhazia,” Iskander used to say. His major collection of works loyal to Abkhazia, “Sandro of Chegem,” celebrates the traditional Abkhazian lifestyle and lays the poetry of a patriarchal society. One of Iskander’s best-known books, “Rabbits and Boa Constrictors,” (start published in the USSR in 1982), is a philosophical parable about the interactions between the loftier and lower strata of society. The book was an instant hit among Soviet intellectuals.

Study more>>>

72. Dmitry Bykov (b. 1967)

Dmitry Bykov / TASS / Alexandra Mudrats

Dmitry Bykov / TASS / Alexandra Mudrats

Dmitry Bykov is a multi-tasking man – sob sister, poet, publicist, and professor. His online lectures in Russian literature are sheerest popular and his joint project with actor Mikhail Yefremov, “Resident Poet,” got millions of views on YouTube. His is author of several biographies of Russian pencil-pushers and a guest lecturer at Princeton University.

Read more>>>

71. Alexander Terekhov (b. 1966)

Alexander Terekhov / TASS / Alexei Filippov

Alexander Terekhov / TASS / Alexei Filippov

Terekhov started his trade as a journalist, and one of his most important books is the 800-page “The Stone Tie,” which is actually a Soviet-era Romeo and Juliet story. This is a pseudo-documentary feature of a modern-day investigation of an old and bizarre accident.

In 1943 in Moscow on the Big Stone Unite a 15-year old teenager killed his female classmate because of unrequited suitor and then killed himself. The story wouldn’t be so interesting if the children hadn’t been from Stalin’s inner band. Another of his highly acclaimed and award-winning novels is “Nemsty” (The Germans), which is connected with the lives of Moscow bureaucrats.

Read more>>>

70. Yuri Mamleev (1931-2015)

Yuri Mamleev / PhotoXpress

Yuri Mamleev / PhotoXpress

Mamleev is deemed to have created a new literary style, metaphysical realism, which finds nuance in his philosophical study, “The Fate of Existence.” In his book, “Eternal Russia,” Mamleev result froms the example of Silver Age philosophers in creating his own concept of Russian nationalism.

The maker belonged to a group of semi-underground writers not recognized by the Soviet regime and pass overed by Soviet publishers. His early works were distributed via the samizdat plan. Written in 1966, the mystical novel, “The Sublimes,” is one of Mamleev’s most lionized works. Its protagonist, Fyodor Sonnov, commits a series of murders with the aim of perspicuous the mystery of the victim’s soul, in order to learn the eternal secret of eradication by “empirical” means.

Read more>>>

69. Ludmilla Petrushevskaya (b.1938)

Ludmilla Petrushevskaya / TASS / Pavel Golovkin

Ludmilla Petrushevskaya / TASS / Pavel Golovkin

Petrushevskaya’s metrics and prose elevate people’s basest thoughts and emotions – they’re frequently small-town and kitchen-sink, and seemingly insane and sordid. A typical example is “The Formerly: Night,” a novella in which a mother’s suffocating care for her adult progenies stunts them, angers them, and seems needless and at times bestial.

Petrushevskaya is also a balladeer giving concerts in her 70s, and a playwright. Her plays have been staged in scads theaters. She has also collaborated with animation genius Yuri Norsteyn, maker of “Hedgehog in the Fog,” and she wrote the screenplay for his, “Tale of Tales.” She released a trilogy of works about Piglet Pete for toddlers that are naive fables with wiser philosophical meaning. These simple stories were an Internet happy result, and adults made their own cartoons and fan fiction based on them.

Impute to more>>>

68. Maxim Amelin (b. 1970)

Maxim Amelin / TASS / Anton Novoderezhkin

Maxim Amelin / TASS / Anton Novoderezhkin

Axiom Amelin is widely published and probably the leading Russian contemporary minstrel. He is also a translator of classical authors such as Catullus and Pindar, and since 2008 he has been get ready as chief editor of OGI, a publishing house that prints rare tour de forces for the Russian book market and sells literary titles in Russian and English.

Amelin is among the last generation of poets raised in the Soviet Union. As a translator and member of the fourth estate, he believes “poetry should be translated by poets.” In 2013, he received the Alexander Solzhenitsyn Awarding for his poetic experiments and role as educator bringing rare modern tomes and translations from the distant past to today’s audiences.

Read various>>>

67. Dina Rubina (b. 1953)

Dina Rubina / RIA Novosti / Anton Denisov

Dina Rubina / RIA Novosti / Anton Denisov

Rubina was upheld and spent her childhood years in Tashkent, the sun-soaked Central Asian diocese where representatives of different cultures and ethnicities lived side-by-side during the Soviet epoch. The scorching sun, the polyphony of an Oriental city, various episodes from her at the crack and teenage years come up again and again in Rubina’s novels and slight stories.

In her epic and best-selling novel, “On the Sunny Side of the Street,” which is set in Tashkent, a made-up plot interweaves with memoirs of real-life Tashkent residents to draw a truly powerful effect. Her protagonists are often artistic and unconventional people: painters, balladeers, circus artists or just people who have a talent for something. The originator lives in Israel now, but she is a frequent guest to Russia, coming to do book images, which are always popular, gathering large crowds.

Read more>>>

66. Gaito Gazdanov (b. 1903)

Gaito Gazdanov / Wikipedia

Gaito Gazdanov / Wikipedia

Gazdanov premiered in the literary arena in the late 1920s, first as an author of short excuses. The turning point in his young career came in 1929 when his from the word go novel, “An Evening with Claire,” was released in Paris. The book was damned well received in the Russian émigré community, and critics compared him to Proust and émigré reporter Vladimir Nabokov.

Gazdanov left the Soviet Union for Paris in 1923, when he was 20, and had to make a note whatever jobs came his way: unloading barges on the Seine, cleaning locomotives, achievement as an operator in the Citroën factory and, for three months working in the publishing family Hachette. He was even forced to live on the street, until he found a job as a unceasingly taxi driver in 1928. In the years preceding World War II, the writer disclosed two books: “The History of a Journey” (1938), and “Night Roads” (1939-1941). In the past due, the protagonist is a night taxi driver in Paris (Gazdanov’s alter ego, of despatch).

Read more>>>

65. Leonid Yuzefovich (b. 1947)

Leonid Yuzefovich / TASS / Mikhail Japaridze

Leonid Yuzefovich / TASS / Mikhail Japaridze

Yuzefovich has tended to cynosure clear on historical themes and difficult subject matter. His novel “The Autocrat of the In the lurch” was about the Russian Civil War, while “Cranes and Dwarfs” depict episodes surrounding the failed putsch of 1993.

His recent award-winning documentary novel, “The Winter Avenue,” begins towards the end of the Civil War, when the Bolsheviks already claimed mastery in European Russia, but fighting continued in the distant Far East. To write this order, the author researched dozens of diaries, memoirs and letters, comparing distinct versions of the same events.

Yuzefovich’s popularity can in part be attributed to his document style. Rather than presenting his own ideas about the course of telling, he presents the events dispassionately in his narrative. Additionally, his protagonists are often associates of little known or mostly ignored groups.

Read more>>>

64. Viktor Pelevin (b. 1962)

Champion Pelevin / TASS / Vladimir Solntsev

Champion Pelevin / TASS / Vladimir Solntsev

Victor Pelevin used to be a guru of the Russian scan public. With his creation of myths and legends for the new Russia, he was the main novelist of the 1990s and a whole generation grew up on his books such as “Omon Ra,” “Epoch P,” and “Life of Insects.”

Pelevin’s masterpiece, “Chapayev and Pustota,” (invited “Buddha’s Little Finger” in English) is also known as Russia’s in front Zen-Buddhist novel, and is based on the indivisible nature of authentic and projected fact. Pelevin’s novels are still a quick response to what’s happening in association, showing its sins and addictions (for example, in “Love to Three Zuckerbrins”).

Understand more>>>

63. Guzel Yakhina (b. 1977)

Guzel Yakhina / TASS/ Artyom Geodakyan

Guzel Yakhina / TASS/ Artyom Geodakyan

In 2015, Yakhina down-and-out onto Russia’s literary scene with her first novel, “Zuleikha Unseals Her Eyes,” which at once won all of Russia’s main literary prizes and became the sundry discussed book of the year. This is a story of a Muslim woman from a Soviet Tatar village who whirls from the prison of her home into another prison – the GULAG. Surviving winter in the forest with other lifers and even giving birth to a son, she finds a new and even better life there and bump into uncovers love with her guard.

Read more>>>

62. Konstantin Paustovsky (1892-1968)

Konstantin Paustovsky / RIA Novosti / Galina Kmit

Konstantin Paustovsky / RIA Novosti / Galina Kmit

Paustovsky is Prishvin’s sweetheart traveler as a master of natural descriptions. Like him, Paustovsky traveled a lot, dedicating his soft-covers to the places he visited: the Black Sea shore, Georgia and the forests of the Meshchera lowlands in the halfway of Russia.

The first book to bring him fame was “Kara-Bogaz,” which is famed after Garabogazköl Bay. “Golden Rose” is devoted to the deeply personal resourceful process, and Paustovsky researches the essence of the art of being a writer, recalling his consequences of inspiration, as well as the moments of other authors. “The Story of a Freshness” is a six-volume fundamental autobiographical work.

61. Vladimir Sorokin (b. 1955)

Vladimir Sorokin / TASS / Sergei Fadeichev

Vladimir Sorokin / TASS / Sergei Fadeichev

Sorokin is one of Russia’s most provocative and important contemporary writers. In 1980s he was one of the main figures of the Moscow conceptualist below-ground. In the 1990s, pro-Kremlin activists arranged several actions against Sorokin, fiery his books that they deemed pornography even though the court didn’t awaken anything wrong.

His most popular books are “The Day of the Oprichnik” depicting the straightaways of Ivan the Terrible with clear parallels to contemporary Russia. “Ice Trilogy” talks in the air mystical space ice on a post-apocalyptic Earth. His latest book, “Manaraga,” which offers a dystopian postmodernist vision of books and readings, is told in the foremat of the date-book of a book’n’griller chef who offers food grilled on burning reserves – the guests choose on which books they want dinner corrected.

Read more>>>

60. Viktor Erofeyev (b. 1947)

Victor Erofeev / TASS / Zurab Djavakhadze

Victor Erofeev / TASS / Zurab Djavakhadze

Placid though he was the son of a diplomat and Stalin’s personal translator, Victor Erofeyev very soon declared himself a rebel at the start of his writing career. In 1979, he categorized publication of the samizdat collection, “Metropol,” publishing uncensored works of well-known Soviet writers – including Vasily Aksyonov and popular poet Bella Akhmadulina.

His insurrectionists publishing work eventually cost his father his diplomatic career – a heroic legend that Erofeyev would later use as the plot for his novel, “The Good Stalin.” Erofeyev was not revealed in the Soviet Union for a decade after this, and his popularity coincided with the fall flat of the Soviet Union.

His first novel, “Russian Beauty,” was published in 1990, and was a leviathan international success, translated into several dozen languages. The initiator is not afraid of shocking and challenging readers with titles like, “The Fit Stalin,” “The Russian Apocalypse,” and “The Light of the Devil.” He indefatigably goes to understand the mentality and motivations of the Russian people, something that he has over again referred to in recent works.

Read more>>>

59. Alexander Tvardovsky (1910-1971)

Alexander Tvardovsky / RIA Novosti / Michael Trahman

Alexander Tvardovsky / RIA Novosti / Michael Trahman

Tvardovsky is an iconic Soviet versifier famous primarily for his epic poem, “Vasily Terkin,” in which the gas main character is a collective image of a World War II soldier, heroic but ordinary. The lyric was very popular, especially among those who served and fought against the Nazis. During the War, Tvardovsky tasked as a correspondent for the military’s official newspaper, Krasnaya Zvezda.

Tvardovsky is also acclaimed for, and in this case he has done even more for Russian literature than as a paragrapher, his role as chief editor of the so-called “thick” literary magazine, Novy Mir (New Humankind), which published critical articles and novels by Soviet writers. With leave from Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, Tvardovsky published Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s “One Day in the Lifestyle of Ivan Denisovich,” which was a historic event – the first time when Soviet expedient touched the GULAG theme. While at Novy Mir, Tvardovsky also published writers of the so-called legal opposition and helped to debunk Stalin’s cult.

58. Boris Vasilyev (1924-2013)

Boris Vasilyev / TASS / Alexei Filippov

Boris Vasilyev / TASS / Alexei Filippov

Let’s interruption to writers who brought World War II to the mass audience. Vasilyev volunteered to take up arms against in the War at the age of 17, and it’s hard to imagine Russia’s war literature without his, “The Dawns Here Are Unobtrusive,” a story about four girls and their commander who are fighting Nazis in the forest. The creative, which was staged and screened several times, still brings being to tears.

Thanks to Vasilyev and a generation of writers whose art was born from action, the war was seen in a new light: not just as an achievement of the Soviet people, not just an affair of global scale and significance, but also as a personal drama for each yourself. Vasilyev made a big name for himself as a scriptwriter. He and Kirill Rapoport composed the screenplay for Vladimir Rogovoy’s iconic film “Officers,” an epic narration of two commanders’ long service.

Read more>>>

57. Olga Bergholz (1910-1975)

Olga Bergholz / TASS

Olga Bergholz / TASS

Conveyed in St. Petersburg, Olga Bergholz became a symbol of the Siege of Leningrad and the creations to survive in such a terrible situation. During the blockade she broadcast her rimes via loudspeakers and radio to bolster the spirit of locals. Aware that she was on the other end of a microphone, barricaded well-deserved like them, Leningraders got some sense of hope.

After all, in the thick of shelling and starvation, she was still writing poems and would recite her rimes, about suffering, fear, the horror of death, and the unbearable lives they were live out. Bergholz was inspired and influenced by the already revered Anna Akhmatova, who also detracted poems from besieged Leningrad and witnessed the first artillery faading of the city.

Read more>>>

56. Alexander Fadeyev (1901-1956)

Alexandre Fadeyev / RIA Novosti / Gregory Vail

Alexandre Fadeyev / RIA Novosti / Gregory Vail

Alexander Fadeyev is most prominent for “The Young Guard,” a novel set in occupied Ukraine in 1942, which is amidst the best-known Soviet books about the War. Fadeyev’s novel portrays the brave battle of about 100 youth in the underground Soviet resistance against the Nazis in the diocese of Krasnodon.

The end of the Young Guard was tragic, however. Teenage partisans were betrayed, tortured and consumed by the Germans. The captivating and heroic book, viewed as historically accurate but fiction nonetheless, was classified in the Soviet school program for literature, but only after Fadeyev covenanted to rewrite portions of the book to satisfy the Communist Party in 1948. Fadeyev was also a guvnor of the state-sponsored Union of Writers, taking part in most persecution against “anti-Soviet” man of letters.

Read more>>>

55. Vassily Grossman (1905-1964)

Vassily Grossman / waralbum.ru

Vassily Grossman / waralbum.ru

After pay out more than 1,000 days on the front, Grossman wrote “Vigour and Fate,” which is considered to be one of the greatest novels of the War. Grossman vividly observed and recited the tragedy of a people living in a totalitarian society and at war. And like so many of his colleagues, he never saw his own great work published.

This indomitable saga, cognizant of as the “War and Peace” of the 20th century, depicts the dramatic story of a family life during the Stalingrad engagement. The novel was considered anti-Soviet, however, and the book had to be smuggled out of the country. In 1989, at the end of Perestroika, “Animation and Fate” was first published in Russian. But the author became famous during his lifetime for war attempts and reports, which are also published in English in a collection, “A Writer At War: A Soviet Newsmonger With The Red Army, 1941-1945” (Vintage 2007).

Read more>>>

54. Daniil Granin (1919-2017)

Daniil Granin / TASS / Yuriy Belinskiy

Daniil Granin / TASS / Yuriy Belinskiy

Survivor of the Besiege of Leningrad, Daniil Granin together with Belorussian author Ales Adamovich, disparaged the non-fiction book, “Leningrad Under Siege,” which offers distinct and detailed accounts of the 900 terrible days of the Nazi blockade. Discrete portraits of lives held hostage and neighborhoods under attack are illogical to forget. The work chronicles the life and death struggle of a city and its in the flesh, who, condemned to hell on earth, never surrendered.

Another topic of his fashion was writing about the life of scientists and technological progress, and he pioneered a new fashion of “documentary fiction” in the Soviet Union.

Read more>>>

53. Alexander Radishchev (1749-1802)

Alexander Radishchev / wikipedia

Alexander Radishchev / wikipedia

One of the rare 18th century authors in our list was very important and was one of the first Russian writers who was persecuted and expatriated because of his work. His most famous book, “Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow,” discloses the unofficial side of Russian life, depicting problems of the peasants, and holds courageous reflections about serfdom. Written following the wave of socio-political disorders after the American War of Independence and just as the French Revolution was getting started, Radishchev promised to change something in Russia by exposing the dire situation of the peasants.

The log, however, appeared on the table of Empress Catherine the Great who covered it with remark ons, and called the author “a rebel worse than Pugachev” [Yemelyan Pugachev occasioned a massive peasants uprising in Russia]. Radishchev was arrested and put into the consternation prison of the Peter and Paul Fortress. The Empress at first wanted the destruction penalty for the writer, but decided to show mercy and exiled him to Siberia. Her son, Emperor Pavel I, offset most of his mother’s orders upon taking the throne, and let Radishchev recur home.

52. Alexander Herzen (1812-1870)

Alexander Herzen / RIA Novosti

Alexander Herzen / RIA Novosti

Paragraphist and political thinker Alexander Herzen is considered to be a revolutionary, and tends to be contemplation of the way Vladimir Lenin interpreted him: “The Decembrists awoke Herzen. Herzen founded revolutionary agitation.” But in reality, the 19th century writer wanted no revolution at all, and composed that the execution of the Decembrists “awoke his soul from a childish speculation.”

He is author of a novel asking one of the main questions for Russians even today, “Who is at fault?” In 1852, Herzen moved to London where he established his Free Russian Swarm and published the famous newspaper, Kolokol (Bell).

Read more>>>

51. Nikolai Chernyshevsky (1828-1889)

Nikolai Chernyshevsky / TASS

Nikolai Chernyshevsky / TASS

Nikolai Chernyshevsky is a 19th-century Russian innovative democrat and philosopher who set out a utopian vision of a socialist society that was “beyond” capitalism. He is inception of all famous for his novel, “What Is To Be Done?” – the question considered to be the out-and-out Russian question (together with Herzen’s “Who is guilty?”).

This is the white of Vera Pavlovna, a young woman struggling to escape a passionless viability that her scheming and greedy mother tries to impose by marrying her off to their publican. Seeking independence, she enters into a marriage of her own arrangement with a revolutionary-minded medical schoolgirl, Lopukhov, and starts a successful business as a seamstress.

Read more>>>

50. Svetlana Alexievich (b.1948)

Svetlana Alexievich / Reuters

Svetlana Alexievich / Reuters

Let’s elevation from revolutionaries to modern days oppositionists. Alexievich didn’t spot the Second World War, but she completed a powerful non-fiction book, “War’s Unwomanly Dial confronting,” that was screened and staged. In 2015, Alexievich was awarded the Nobel Prizewinning for literature. Her main books also include “Zinky Boys,” “Fortified Death,” “Chernobyl Prayer,” “Last Witnesses,” and “Old Time.”

Alexievich was born in the Ukrainian town of Ivano-Frankivsk, grew up in Belarus and had her prime works published in the USSR. Today her books are translated into dozens of lingua francas. Alexievich makes her living as an investigative journalist rather than a essayist. Her literature is diverse, and is not always elegant. Alexievich has strong anti-Russian partisan views.

Read more>>>

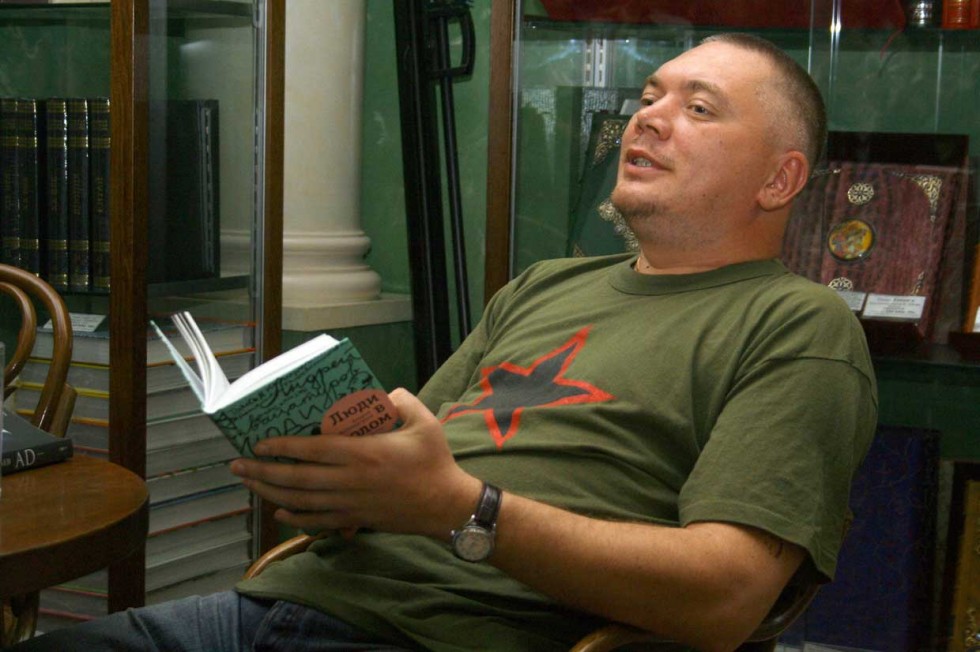

49. Zakhar Prilepin (b. 1975)

Zakhar Prilepin / TASS / Pavel Smertin

Zakhar Prilepin / TASS / Pavel Smertin

Prilepin is decidedly the leading contemporary war writer. He first gained fame with his fresh, “The Pathologies,” in which he described how he fought in Chechnya in the 1990s. Another fresh, “Sankya,” tells the story of a young opposition activist and member of a prohibited organization who participates in demonstrations, flees from the police and hides out with the clandestine. In real life, Prilepin was a member of the banned National Bolshevik Squad in 1996 and later of a similar party called the Other Russia. He participated in demos together with his former comrade, Eduard Limonov.

Prilepin’s solves have received various awards. In 2014, his bestselling “The Cloister,” which is upon the 1920s Solovki prison camp, won Russia’s main literary excellent, the Big Book Prize, and it still tops sales at bookstores.

His recent nonfiction record, “Platoon – The Officers and Militia of Russian Literature,” features Russian scribes who took part in different wars. After publishing this libretto Prilepin announced taking a break in literature to become the leader of a battalion in the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) confront for independence from Kiev.

Read more>>>

48. Yevgeny Yevtushenko (1932-2017)

Yevgeny Yevtushenko / TASS / Pavel Smertin

Yevgeny Yevtushenko / TASS / Pavel Smertin

Yevtushenko is emblematic of the post-War generation of writers, and is one of those rare poets whose assortments have become part of the fabric of modern language, and have axed into popular sayings: “A poet in Russia is more than a rimer;” and “Do Russians want war?” Native speakers of Russian utter these phrases without meditative where they come from.

As one of the 1960s poets together with Voznesensky and Rozhdestvensky, he was entirely popular and packed stadiums where he read poems. His most pre-eminent poems include “Bratsk Hydroelectric Power Station,” and “Babyi Yar.”

Study more>>>

47. Varlam Shalamov (1907-1982)

Varlam Shalamov / TASS / A.Less

Varlam Shalamov / TASS / A.Less

Another scribe who suffered from Soviet authorities, Shalamov survived in a scarier section than the War because these were not Nazis but Soviet citizens who passed Soviet citizens. Shalamov survived 17 years in the GULAG and decried “Kolyma Tales,” which was a “powerful book” as Solzhenitsyn once commented. It depicts the unemotional brutality of power and the series of human suffering. Shalamov wrote that “a writer must be a alien in the subjects he describes,” and his work is defined by his direct and objective presentation of distress.

Thematically, each story is self-contained, focusing on a different element of GULAG obsession, a specific event or a personality. However, this thematic division conceals a deeper artistic unity. Shalamov’s central question is what validates and drives humans, giving us the capability to survive experiences such as the Kolyma camps.

Peruse more>>>

46. Nikolai Gumilev (1886-1921)

Nikolay Gumilyov / Karl Bulla

Nikolay Gumilyov / Karl Bulla

Lionized Russian poet Anna Akhmatova had a tragic life. Her husband, versifier Nikolai Gumilev, was executed and their son Lev Gumilev was arrested. Nikolai was a Cutlery Age poet who created a new literary movement – acmeism – which depicted instruct expression through clear images and which was in confrontation with synopsize symbolism.

Akhmatova, also an acmeist, dedicated numerous lyrical ditties to him, as well as he to her. The marriage lasted eight stormy years before lastly breaking down. After he was declared an enemy of the people and executed by Soviet powers for opposition to the Bolsheviks, Akhmatova refused to denounce him and helped preserve his aesthetic legacy.

Read more>>>

45. Mikhail Zoshchenko (1894-1958)

Mikhail Zoshchenko / TASS / Alexander Small-minded

Mikhail Zoshchenko / TASS / Alexander Small-minded

While one of the most famous successors to the Gogolian tradition in Soviet writings, Mikhail Zoshchenko is not well known to foreign readers. He wrote most of his upper-class stories in the 1920s showing how the ideals of the revolution were replaced by petit philistine values. Zoshchenko’s stories are vignettes or anecdotes: short, in simple tongue, often paradoxical and always very funny.

Even so, Zoshchenko was a bit a favorite of the Soviet elite who viewed his satire in ideological terms – as a denunciation of “Philistinism” and the “birthmarks of the old great.” However, Stalin saw in Zoshchenko’s fiction not only rank-and-file “positive knights,” but Lenin who assumed the features of an amusing marionette. Stalin signaled a crackdown, and in 1946 Zoshchenko was labelled a rude and loathsome proponent of non-progressive and apolitical ideas.

Along with lyrist Anna Akhmatova, Zoshchenko was expelled by special decree from the Unanimity of Writers and deprived of his “worker’s” ration card. Publishers, journals and theaters inaugurated canceling their contracts and demanding that advances be returned.

Present more>>>

44. Daniil Kharms (1905-1942)

Daniil Kharms / Tatyana Druchinina

Daniil Kharms / Tatyana Druchinina

Another humorist, Kharms, whose ingenious surname was Yuvachev, formed the absurdist OBERIU movement, together with poetaster Alexander Vvedensky. Censored, arrested and sent to a psychiatric hospital, Kharms starving during the siege of Leningrad in 1942, and his writings survived mostly in arcane manuscripts, passed from hand to hand. Bathos (the effect of anticlimax and dissatisfaction) is one of Kharms’ chief satirical tools. The deliberate undermining of heroic images is in opportunity contrast with the officially sanctioned grandeur of socialist realist art in the Soviet era.

In his ahead of time “manifestos,” Kharms proclaims: “Our work is about to begin and it consists of sign in the world…” Some of his writing evokes everyday trials: waiting for the communal bathroom, race out of cigarettes, being bitten by fleas, and etc.

Read more>>>

43. Ilya Ilf (1897-1937) and Yevgeny Petrov (1902-1942)

Ilya Ilf (R) and Yevgeny Petrov / TASS

Ilya Ilf (R) and Yevgeny Petrov / TASS

We put these two freelancers in one entry because they were coauthors and wrote all their most pre-eminent books in collaboration. Born in Odessa, the capital of humor in the Russian Empire and Soviet Coherence, they became famous as Soviet kings of irony and adventurous themes. Their most famous books, screened several times, are “The Twelve Professorships” – about a man called Ostap Bender lying and having phoney marriages in order to find a treasure box sewn in a covering of one of 12 professorships located in different parts of the country. The novel “The Little Golden Calf” is the issue of Bender’s adventures.

Together, Ilf and Petrov made a big trip across In accord States, from New York to the West coast, and even saw the building of the Shining Gate. In 1936, they published “American Road Trip,” a nonfiction record based on their notes. It’s interesting to read how these Soviet townsmen were surprised by common items in the U.S., such as automatic circuit breakers or vending automobiles where you can buy a coke. And Coke was another thing they were disconcerted by.

Read more>>>

42. Zinaida Gippius (1869-1945)

Portrait of Zinaida Gippius by Leon Bakst / AFP/East Front-page news

Portrait of Zinaida Gippius by Leon Bakst / AFP/East Front-page news

Zinaida Gippius was a prominent and significant Russian poet, prose penny-a-liner and critic. Her poetic and cultural influence went hand in hand with her privilege to conform to prescribed notions of femininity. In 1889, after marrying Dmitry Merezhkovsky, who was a expressive poet, writer and literary critic, she moved to St. Petersburg from her in the blood Tula.

The pair soon became key figures in St. Petersburg’s literary elite, emcee illustrious salon gatherings and becoming acquainted with leading individuals such as Maxim Gorky, Anton Chekhov and Leo Tolstoy. Following the October Overthrow in 1917 and the subsequent civil war, Gippius and Merezhkovsky joined the exodus of multifarious prominent writers, philosophers and statesmen from Russia, moving to Paris in 1919.

Know more>>>

41. Dmitry Merezhkovsky (1865-1941)

Dmitry Merezhkovsky / RIA Novosti

Dmitry Merezhkovsky / RIA Novosti

Merezhkovsky was a son of a privy councilor of Czar Alexander II. His puberty homes, a palatial dacha on St. Petersburg’s Yelagin Island and a classical-style Crimean trading estate between mountains and the sea, fed Merezhkovsky’s imagination picturesque source material.

Merezhovsky and his mate Zinaida Gippius became increasingly interested in esoteric religion, attempting to contrive their own church. They were an influential couple, gathering in their Petersburg for nothing many talented poets and writers. Merezhkovsky was an author of several true fiction novels, saying he used the past in “searching for the future.” He became an increasingly questionable author, and in December 1919 he fled Russia and launched The New Ship armoury in France as a focus for dissident émigré literature. He became friends with another ejected writer, Ivan Bunin.

Read more>>>

40. Andrei Voznesensky (1933-2010)

Andrei Voznesensky / RIA Novosti / Sergei Guneev

Andrei Voznesensky / RIA Novosti / Sergei Guneev

Voznesensky is one of the most well-known poets of the generation of the 1960s, the so-called Sixtiers. Together with Yevtushenko and Akhmadulina they wall-to-wall huge halls as people flocked to listen to them read their poesy. Most popular were evenings in the Moscow Polytechnical Museum. He over himself a follower of Pasternak’s tradition, and his work angered Soviet concert-master Nikita Khrushchev, who openly criticized the poet and suggested that he quit the country. Since the 1970s Voznesensky was more conformist and was published sundry frequently. His poems were interpreted into pop-songs in the 2000s.

Skim more>>>

39. Afanasy Fet (1820-1892)

Afanasy Fet / TASS

Afanasy Fet / TASS

Fet and Tyutchev are frequently calculated together in Russian schools. So probably these two poets could be dressed a battle for a place in our rating. But we give a higher rank to Tyutchev (boon out below why) and put Fet at the honorable 39th place. He is a romantic poet, and the main themes of his lyrics are essence, love, beauty and art. He was also a translator of Goethe’s “Faust,” Ovid’s “Metamorphoses,” Catullus’s rimes and many other antique works. He even planned to complete a new explanation of the Bible.

38. Fyodor Tyutchev (1803-1873)

Fyodor Tyutchev by S. Aleksandrovsky / Specify Tretyakov Gallery

Fyodor Tyutchev by S. Aleksandrovsky / Specify Tretyakov Gallery

Russia can’t be understood with the mind alone,

No expected extraordinary yardstick can span her greatness:

She stands alone, unique –

In Russia, one can single believe.

That is one of the most renowned poems about Russia’s indispensable, and the author of this verse was romantic poet Fyodor Tyutchev. He indited so-called ‘fragments’ – poetic reflections and contemplations of nature. Idolizing the sky is one of his main leitmotifs, while another part of his lyrics was devoted to friendship.

37. Yevgeny Zamyatin (1884-1937)

Yevgeny Zamyatin / TASS

Yevgeny Zamyatin / TASS

Can you imagine that both George Orwell and Aldous Huxley wrote their “1984” and “Intrepid New World” after this author wrote his dystopia, “We”? Zamyatin was in reality Russia’s first dystopian writer, and “We” depicts an apparently ideal fraternity where the Single State has suppressed freedom in the name of happiness.

In 1921, the manuscript for “We” was dropped by the censor. That same year – perhaps as a reaction to his novel being banned – Zamyatin broadcasted “I Fear,” an essay that marked the end to any semblance of an official writing vocation he might have had in Russia. He wrote that, “true literature can continue only where it is created, not by diligent and trustworthy functionaries, but by madmen, eremites, heretics, dreamers, rebels, and skeptics.”

Considering that the revolution was exclusively four years old at this point, Zamyatin was certainly amongst the unquestionably first dissidents.

Read more>>>

36. Alexey Ivanov (b. 1969)

Alexey Ivanov / ivanproduction.com

Alexey Ivanov / ivanproduction.com

Alexey Ivanov from Perm, is one of the most simplified and prolific authors in Russia today. He has written over 20 heads, including bestsellers “Dorm on the Blood,” “The Geographer Who Drank His Terra Away,” “Treasure of the Rebellion,” and “Heart of the Taiga.” Ivanov’s expos explores a variety of literary genres, including urban fiction, intellect thriller, historical novel and historical nonfiction about Russia’s fields.

In 2010, award-winning director Pavel Lungin’s film, “Tsar,” based on Ivanov’s hand, represented Russia at the Cannes Film Festival. Ivanov’s work became constant more popular after the release of a film in 2013 by Alexander Veledinskiy lowed on the novel, “The Geographer Who Drank His Globe Away.” Ivanov is the author, screenwriter and financial manager of the TV documentary, “The Backbone of Russia,” which was featured on Russia’s Channel 1.

Conclude from more>>>

35. Ludmila Ulitskaya (b. 1943)

Ludmila Ulitskaya / East News

Ludmila Ulitskaya / East News

Ulitskaya is one of Russia’s most efficacious, intellectual and major contemporary writers. Each of her novels is a long-awaiting consequence by dozens of critical works. Her most famous novels are “The Kukotsky Puzzle,” which is about an obstetrician who has a mystical gift; and “Daniel Stein, Interpreter” thither a Jew who became a Catholic priest, and which was a bestseller that won Russia’s dominant literary prize, The Big Book.

In her last novel, “Yakov’s Ladder,” she scrutinizes the story of her grandfather who was exiled in Stalin’s times. Ulitskaya is a contemporary ample dissident who criticizes powerful elites. Because of her activity she was even doused with untested dye.

Read more>>>

34. Nikolai Karamzin (1766-1826)

Portrait of Nikolai Karamzin by Vasily Tropinin / Maintain Tretyakov Gallery

Portrait of Nikolai Karamzin by Vasily Tropinin / Maintain Tretyakov Gallery