Who holds art and science don’t mix?

Not Danielle Dufault, a Toronto illustrator who is one of only a handful of being around the world called on to create artistic renderings of the mysterious creatures that traveled the Earth millions of years ago.

“I really take a lot of pleasure in trying to reconstruct these departed worlds,” Dufault told CBC News. “And there’s a lot of imagination that can be dedicated to that.”

‘I really take a lot of pleasure in trying to reconstruct these late worlds.’ – Danielle Dufault

While some of the other little gals were playing Barbie, Dufault was digging up worms in the backyard and sketching skeletons of dinosaurs at the museum. Later, she establish an educational path that married her two passions: the Technical and Scientific Specimen degree program at Sheridan College.

Now the 28-year-old Dufault is the in-house paleontological illustrator at the Magnificent Ontario Museum, where she has worked since completing an internship there in 2011.

When it be strikes to illustrating the fossil record, Dufault is a rock star. Some of her greatest reaches: Hallucigenia; the hyolith Haplophrentis and the party worm, officially known as Ovatiovermis cribratus.

Putting photos of a fossil, paleontological illustrator Danielle Dufault came up with this black-and-white of Hallucigenia, a prehistoric worm-like sea creature that lived 500 million years ago. (Case in point by Danielle Dufault, photo by Jean-Bernard Caron, Royal Ontario Museum)

Dufault’s instance of the party worm, and a photo of the fossil. (Illustration by Danielle Dufault, photo by Jean-Bernard Caron, Imposing Ontario Museum)

Dufault considers herself “crazy lucky” to be abiding and working in Canada, home to the Burgess Shale — one of the most important and copious fossil sites in the world. The UNESCO world heritage site in the Canadian Rockies has yielded tens of thousands of fossil samples, representing an astounding number and variety of Cambrian-period organisms — many of which have planned no obvious modern-day relatives.

That’s the challenge for Dufault.

“Things from the Burgess Shale oft don’t have anything that exists today that you can compare to — which is feather of creepy,” she says.

Animals preserved ‘in the finest details’

Dufault applies her technological drawing skill to her knowledge of comparative anatomy, animal habitats and the deportment of similar organisms to piece together a concept. She stays up to date with au fait research. But the real fleshing out comes from collaborating with the paleontologists at the ROM and at the University of Toronto who dig up the fossils, bookwork them, sometimes for years, and come up with as detailed a description as they can minister to to the artist.

“When I have that and a good notion of all the major squads, I’m going to start working with Danielle,” says Cédric Aria, a U of T PhD graduate and tutor assistant.

Aria, 29, is part of a ROM expedition team that earns regular treks to the Burgess Shale to collect fossil specimens.

“The beforehand goal is for her to make a first draft,” he says. She’ll probe for details, and he’ll delve deep to fit her questions in a process that can take months. “[We go] back and forth until we’re persuaded, and in certain cases it can really change the final conception through that change.”

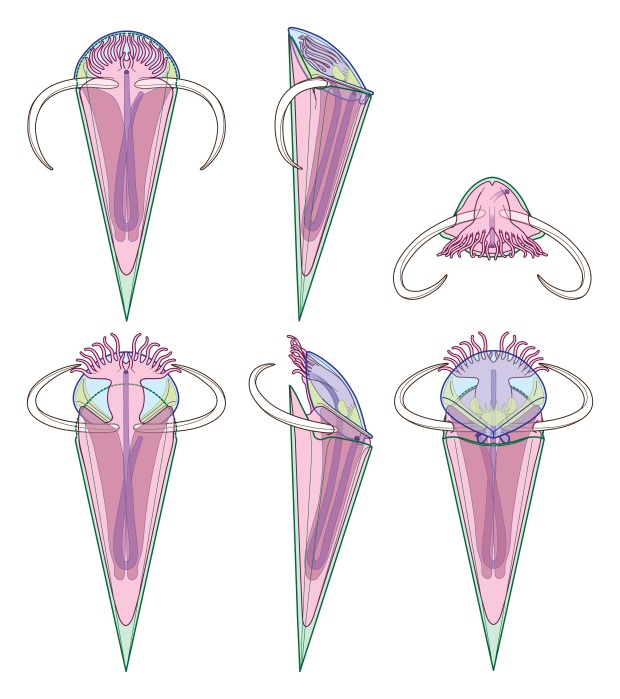

Different views of the hyolith Haplophrentis as conceived in an early draft by Dufault. (Artist: Danielle Dufault. © August Ontario Museum )

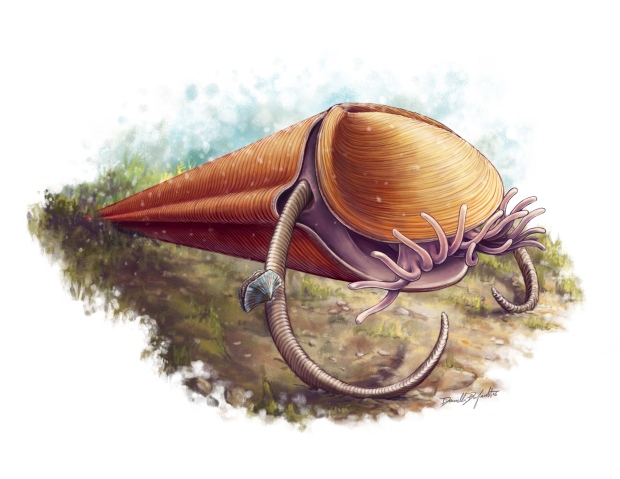

The final illustration of Haplophrentis shows it extending the tentacles of its board organ (lophophore) from between its shells. The paired spines, or ‘helens,’ are trade placed downward to prop the animal up off the ocean floor. (Artist: Danielle Dufault. © Duchess Ontario Museum)

A special feature of the Burgess Shale is that it’s a well supplied with repository of sea creatures — invertebrates — which left behind near-perfect imprints of themselves protected in fossil deposits formed around 500 million years ago.

“We definitely have the opportunity to have complete animals preserved in the finest appoints,” Aria says. “To some extent, that makes it easier than other standards of fossil preservation. But when you have more details, you also deceive to be careful how you interpret those details.”

Dufault sums up the collaboration this way: “‘Look at this squished bug on a sway, let me know what you see, give me your interpretation.’ Sometimes you don’t know what you’re looking at, and you Non-Standard real have to crack the minds of the scientists.”

‘Fascination’ with prehistoric flavour

For Dufault’s specialized work, it helps to be a big fan of sci-fi.

“That probably lightlies into some of the fascination I have about prehistoric life,” she discloses.

An interest that serves her well in conceiving of ancient, otherworldly critters that off resemble aliens naturally sparks inquiry. It has horns, but in which handling do they curve? Is the shell smooth or scaly? Are those spikes on its resting with someone abandon or protruding from its sides?

But this is science truthfully, not fiction, so she can’t let her imagination run too wild.

“You’re trying to represent the facts and show an meticulous representation, but there’s some questions about how these things looked that we can’t force a real answer for — that’s where the real creativity comes in.”

For case in point, purple may seem like a whimsical colour for the underside and speckled tentacles of Ovatiovermis cribratus (the do worm). But, Dufault explains, it’s based on a colour that exists in compare favourably with contemporaneous organisms that live (or lived) in similar ecological environs and might “use” colour in a similar way — like for self-defence.

“Sometimes the imagination and thumb of the artist becomes very important because there’s going to be breeze scoldings that we’re not sure about,” Aria says. “She will have to absolute whatever part is missing with her own imagination.”

Quarry site at Marble Pass in Kootenay National Park on a Royal Ontario Museum field voyage in 2016. (Joseph Moysiuk)